As I write this blog a couple weeks after attending the Black in School book launch and listening to the panelist Genevieve MBE who has accomplished so much in education, I feel it would be remiss not to share my reflections on an issue affecting young people nationwide.

The attainment gap continues to widen between our most disadvantaged pupils and their peers. Pupils from socially deprived backgrounds statistically perform significantly worse than those from more affluent families by the end of Year 11. According to the latest Department for Education data (2023–2024), only 25.2% of disadvantaged pupils achieved a grade 5 or above in English and Maths compared to 52.4% of non-disadvantaged pupils, a gap of over 27 percentage points.

There’s been a lot of discussion about this over the years. We’ve spoken for a long time about closing the gap for priority groups such as BCRB, FSM, and PP students, but the outcomes don’t seem to reflect that effort. These pupils still aren’t receiving the academic outcomes they deserve.

As educators, we have a duty to give these pupils a genuine platform to succeed so they can leave school with the strong academic outcomes they need to compete for places in grammar schools, apprenticeships, and sixth forms alongside their more advantaged peers. The strategies we use in schools must go beyond theory; they must have a transformative impact.

There needs to be a unified, intentional focus to support these pupils, especially those growing up in communities where they are often one of the only ethnic minority individuals, leading to feelings of isolation and marginalisation, which impacts their academic achievement and personal development in the long term.

We often speak about belonging and inclusion, and I’ve worked in schools where “family” and “togetherness” are promoted as core values. But these ideals don’t always translate into pupils’ lived experiences.

I know this firsthand. I was a young, dark-skinned Black boy of Nigerian descent, growing up in a socially deprived area of South-East London. I didn’t realise how profoundly my skin colour would shape my experience. Even in environments where others looked like me, I still didn’t feel I belonged. That absence of belonging impacted my identity and outcomes, with me being effectively permanently excluded at the start of the Spring Term of Year 11. Despite these tribulations, I still exceeded my predicted grades and managed to get 5 GCSEs at a time when only 21% of my peers achieved this feat (not exclusive to English and Maths).

Now, as someone who’s worked as a teacher, middle leader, and senior leader, I know the barriers facing disadvantaged pupils. I’ve seen how deeply these challenges affect mental health and academic outcomes. The research on Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) highlights that children who face four or more traumatic events are at increased risk of behavioural, physical, and mental health issues throughout life (Rhodes, Long, Moore et al., EEF, 2019).

This was really thought-provoking. Because I have primarily worked with secondary school pupils, I had, rather naively, overlooked how a child’s experiences in their formative years can profoundly impact their educational trajectory. We need to be a driving force behind bridging the gap between pupil behaviour and academic success, starting in primary education.

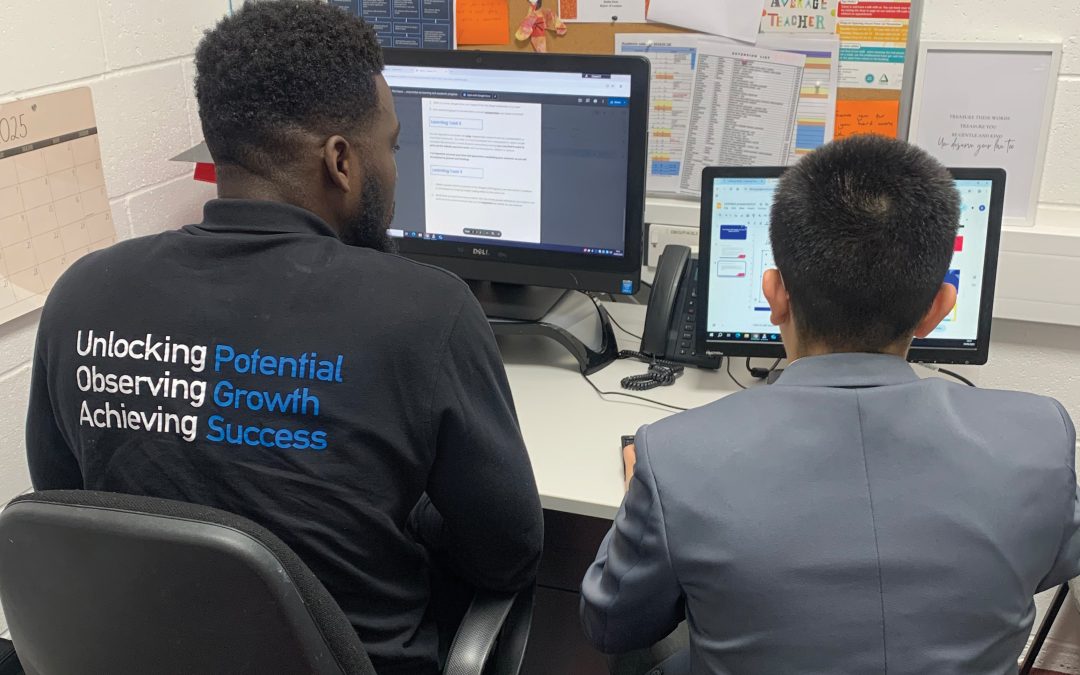

This is primarily the reason why I founded PGS-Educators this year. We deliver specialist initiatives that develop character, build cultural capital, and empower young people to achieve their goals, regardless of background or socio-economic status.

A significant number of young people growing up may encounter complex issues that directly impact their everyday lives. I’ve worked with many pupils who felt there was no relatable forum to receive support while these issues were actively unfolding. This often leads to emotional suppression and decisions that can dramatically alter their life trajectory. Based on my early career experiences, the realisation of this was decisive in shaping my understanding of how incorporating the arts, particularly drama into behaviour interventions can play a vital role in helping young people manage external stress while striving to succeed at school.

Our flagship intervention, True Stories, tackles real-life issues such as gang violence, domestic abuse, bereavement, parental substance misuse, and sexual exploitation, building emotional literacy, resilience, and academic engagement in the process.

According to the latest DfE data (2023–2024), suspensions have risen by 21%, and permanent exclusions by 16%. The need to find scalable solutions to address this challenge, in addition to persistent absenteeism, is clear. We need early, sustained intervention to bridge the gap between behaviour and academic success, starting in primary.

At PGS-Educators, we’re just getting started. We’re committed to working with schools and leaders nationwide to change the trajectory of young lives. This mission is personal because I know what it’s like not to feel adequately supported to be able to thrive.